Moving the dial on critical minerals

The UK Critical Minerals Association and The Geological Society Business Forum hosted their second annual conference on ‘Delivering the UK’s Critical Mineral Ambitions’ focused on implementing the government’s strategy on the topic. Alex Brinded reports.

The UK Critical Minerals Association co-founder Kirsty Benham kicked off proceedings at its annual conference by asking, 'What can the UK implement, in policy and in practice, to push the dial forwards and tangibly develop secure, responsible, critical mineral supply chains? How can other countries work together to build on our strengths?'

The Vice Chairman of consultancy Wood Mackenzie, Julian Kettle, gave a short, sharp shock of a presentation, outlining the scale of the issues confronting the world. 'If you want to generate, transmit, store and use local energy, you can’t do it without metals. That’s a problem for policymakers and for society, because most don’t understand that if you don’t grow it, you mine or extract it – that is an inconvenient truth for them.'

Kettle described how each new natural resources vertical, such as renewable energy and carbon capture, requires massive amounts of metals to increase supply and are interlinked. 'People say what the hell have metals got to do with hydrogen catalysers. If you want to create green hydrogen, you need platinum group metals (PGMs), [but] there are only three places you can go on the planet for PGMs: Russia – high risk, Zimbabwe – high risk, and South Africa…That will require a sea change in catalyser technology.'

In the driving seat

Kettle also questioned the 2.5°C base case driving policy. 'My message here is the policy needs to drive actual change – 1.5°C requires a truly transformational reduction in carbon.'

In the existing base case, he asserted a need to double renewable power generation, whereas at 1.5°C, 'we need to quadruple renewables'. He reminded the audience that renewables have typically four or five times the intensity of metals than typical hydrocarbon generation.

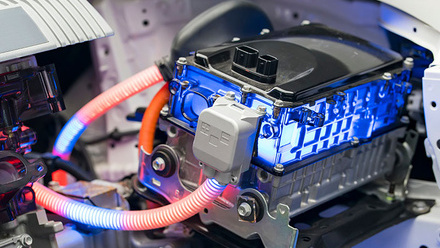

He also outlined how current storage capacity can only last 10 minutes but needs to be 12-14 hours. And there were seven million electric vehicles globally in 2021, while 25 million need selling by 2025 and 45 million by 2030 to hit all our net-zero targets – the impending recession, however, will affect the choices and buying power of middle-income earners.

'We need to invest US$350bln [globally] by 2030. And that’s just in the battery manufacturing capacity.'

In terms of meeting the 2.5°C scenario base case in metals, he pointed out that US$200bln in investment was needed by 2030, and US$325bln for an accelerated energy transition. But investors are not taking the plunge in a recession.

“'It seems to be a surprise to policymakers and investors that to deliver tonnage, and we’re talking about mine supply or refined metal supply, you’re looking at lead times that are three-to-five years from the start of construction. If you include feasibility and then discovery, you’re looking at 10-to-15-year lead times'. Kettle highlighted that capital investment has flatlined in the last seven years in supply.

'We need to invest a truly astronomical amount of money to deliver the mine supply and the refinery supply. This isn’t [just] about battery manufacturing capacity…when we start to think about delivering the transition by 2050…[it is] a US$1.2trln opportunity.'

Kettle noted that, except for copper (as it is a different market), almost any commodity that is exposed to the energy transition will be in boom time from the mid-decade onwards due to policy driving demand ever faster. He envisions running into 'constraints', taking 10-15 years at least to replace China’s supply. He concluded, 'Policymakers need to start to deliver finance, we need partnerships.'

Buckled in

Matt Hatfield is the Critical Minerals Lead for the UK Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), which wrote the government’s Critical Minerals Strategy released last year and sees it as a key risk to the UK’s net-zero ambitions by 2050. Hatfield emphasised that the government recognises the need for these minerals to build renewable energy capacity, plus hydrogen and carbon capture. 'We want to manufacture some of them in the UK and we need minerals therefore in the UK to produce those technologies.'

Ros Lund, who was the Responsible Mining Lead from the UK Department of International Trade (DIT) at the time of the event, observed that the COVID-19 pandemic drew particular attention to the issue of minerals supply. 'The supply was restricted so that gave an impetus when all the policy announcements were made, and of course, the integrated security review alluded to critical minerals.' She flagged that the updated review, due in March 2023, would have a greater emphasis on critical minerals.

Another representative from DIT, Joseph Mansour, Critical Minerals and Net Zero Lead, spoke of the shared impetus across government. 'In two or so years, since government started focusing on this, we’ve gone from a situation where it has been a lot of internal work behind the scenes to get senior decision-makers and ministers to understand the importance of critical minerals, to a point where at the Rio Tinto reception [in November last year], we had two government ministers representing two different government departments, talking about the importance of critical minerals.'

Hatfield crystalised what he sees as the challenge. 'The strategy is setting out the government’s approach to increase the resilience of the supply chains and thinking about how we can secure supplies for manufacturers in the UK, that is really where it stems from.

'We recognise that it’s not practical or desirable to try to onshore the whole supply chain in the UK, or even the majority of it. We need to be pragmatic about targeting areas where the UK has specific competitive advantage and leveraging the expertise the UK has. We talk a lot about the mining heritage and the mining expertise. We [also] talk about the chemical engineering and metallurgy expertise that we have in the UK.'

Mansour highlighted that, 'It is only by sticking with these high environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards that we can actually ensure the security of supply, because so often we have seen how security of supply has been disrupted because of revelations about poor ESG standards'.

Indeed, Lund postulated that ESG in fact makes the UK attractive for foreign companies, mentioning a Canadian company that is set up in the UK because London is an ESG hub despite having no operations here. 'The UK offer is that London is mining finance capital – we have all the services that support that.'

Round the table

To deliver the UK’s Critical Mineral Strategy, Hatfield’s team at BEIS convened an expert committee for advice, chaired by the department’s Chief Scientific Adviser and attended by several IOM3 members..

Francis Wall, Professor of Applied Mineralogy at the Camborne School of Mines at the University of Exeter, UK, contributed to these discussions. 'We warned that there’s more to life than batteries because we keep talking about batteries all the time but of course in critical minerals, there’s niobium and all kinds of things. We talked a lot about sustainable development…about the need for speed and longer-term research. And the fact that critical minerals are individual supply chains. And so, you’ll have to deal with each of those individually, if you really want to create that value chain.'

Cornish Lithium CEO, Jeremy Wrathall FIMMM, pointed out that there was a '…very broad spectrum [of people on the committee] – academia right through exploration, metals experts, PGM experts...I think that very much, while it is government’s role to help, it’s not government’s role to fix necessarily. It is really about how do government and industry work together.'

Another sitting member was Corporate Finance Partner Guy Winter, at mining and minerals firm Fasken. He added, 'You’re not trying to create this supply chain in a vacuum. It has to continually evolve and support the downstream industries. This is a market that has been distorted by extremely powerful forces in terms of the sheer level of investment that’s gone into it in China, not matched by us over decades. I do think there’s an urgent need to consider how you reset that market.'

He outlined that the UK does have a fixed timetable. There is the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement that actually sets rules of origin, which will come in and impose tariffs on exports from the UK. He continued, 'We should actually be working back on that legislative agenda and figuring it out…we ought to have started a couple of years ago…we really have to work with that kind of urgency in mind.'

Darryn Quayle FIMMM, Vice President at engineering company Worley, chaired a panel at the event on giga factories, highlighting that they cost '… several billion pounds each and 25-30% of them are unviable according to some calculations. So, it is pretty important to get the supply chain up to it. Unless the UK Government get their power price down to something reasonable, they haven’t got a snowball’s chance in climate change of having anything in this country.'

Responsible mining

Quayle acknowledged the need for massive amounts of mining in the race to zero, but mining has not perfected zero-impact yet.

Ellen Lenny-Pessagno, Global Vice President of Government and Community Affairs at Albermarle, spoke of her company’s developments in Chile, Australia and the US, and projects under progress in Argentina. She said, 'Responsible mining is so critical, because as we make the transition to green transportation, there’s a lot of eyes looking at mining, I would say much more so than ever looked at oil and gas…we always want to do things the right way.' She cited the example of how 3.5% of the company’s sales are shared with nearby indigenous communities at one site, however, 'it’s really not enough for a company to talk about what they’re doing because nobody believes you'.

Accordingly, Albermarle adhere to standards set by the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance, developed by impacted communities, NGOs, unions, and minerals and mining companies. 'We need to deliver what societies are asking for. And part of it is transparency. A lot of it is even greater engagement with communities. It’s been an intense journey for us, but it’s been such a positive influence on our operations. And our teams are so excited about it. Us being certified with the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance means that we’re going to be able to attract better and more inspired employees.'

Nick Wells, Global Senior Purchasing Manager at the Jaguar Land Rover & Tata Group Battery Programmes, identified three key constraints – capacity, CO₂ and ESG together, and cost. 'The sort of standards we’re talking about, must have a roadmap. They must be credible – they have to be fully traceable. But they can’t set a barrier that is so unattainable that the capacity is not going to be there or is going to be there only for the very highest bidders.'

George Donne, Vice President of Business Development at iyani Metals, discussed his company’s battery-grade manganese project in Botswana, and that most manganese goes to the steel industry as less than 0.5% is of high enough purity for batteries. 'Ninety-five per cent of [that] capacity…sits in China. We’re one of the first new projects outside of China being developed. Because it’s all hydro-metallurgically based, we’ve got a very low-carbon footprint. We believe that we will be a very attractive potential supplier to an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) looking for non-Chinese sources with a low-carbon footprint, hopefully higher levels of sustainability.'

Quayle asked how companies 'were going to magic up the supply chain, when it normally might take 16 years. How do you compress it to five? Is that possible with exploration drilling?'

Lenny-Pessagno said, 'You can’t shorten the time for environmental studies, baseline studies and community engagement… you can’t shorten the time you spend with the community...I do think there’s an opportunity for governments to be a lot more efficient. Australia is a great example of a mining jurisdiction where you can permit much faster.'

Milan Thakore, Market & Strategy Manager at Green Lithium, described how his company is building a merchant lithium refinery in the North of England with integrated projects to address the supply gap. 'Being a new company, we can start with a blank page and get lifecycle assessment studies to try and start production with the lowest carbon footprint as possible. It’s not only down to the miners to ensure that they’re certified – every OEM and battery maker are saying we want to see the feedstock certified.

'We want all the players around the table…I think the OEMs, cathode producers and refiners are all coming to terms that this might be a better way than at each stage everyone wanting to secure different parts and different raw materials.'

Wells shared that he had been working with a small team for the last year at Tata Motors securing upstream critical minerals. 'There’s a lot of different models on integration – cathode makers going upstream to precursors upstream to sulphates, miners going downstream to sulphates to hydroxide and so forth.'

Lenny-Pessagno feels the challenge is new resources because they are so expensive, 'and there’s no visibility on what the price will be 15 years out. And so, we’ve got a real bottleneck there…The question is, is the market serving the development of those resources today?'