Keeping it safe

Safety professionals in the quarry, nuclear, automotive and oil and gas sectors share their experiences.

Clockwise from top left, Rachel Gee, Dr Jagdish Keshav Jethwa, Katherine Evans and David King

© Rachel Gee, Dr Jagdish Keshav Jethwa, Katherine Evans and David King

Rachel Gee, Head of Environment, Health and Safety at Amentum’s Technology & Innovation business unit, where she has responsibility for the Birchwood Park campus in Warrington – the UK’s largest commercial laboratory complex serving the nuclear industry.

How did you get into a career focusing on safety?

I began my career at Siemens in the pharmaceutical sector, initially working in a manufacturing lab before progressing to a senior team role. Siemens had a strong environment, health and safety (EHS) culture. I became an EHS representative for my department, contributing to risk assessments, control of substances hazardous to health (COSHH) assessments, process safety and safety training.

Seeking a new challenge, I explored opportunities in EHS and arranged a meeting with the site EHS manager. With her guidance, I identified key skills to develop and completed the IEMA Certificate in Environmental Management. When a position opened in the department, I transitioned into the role. Later, I expanded my experience by moving into the nuclear sector. A career in EHS has given me the opportunity to travel and work with diverse teams across sectors.

My initial interest stemmed from the environmental aspect. With a degree in Zoology and Marine Zoology, I was excited to apply my academic background.

What skills and training were required?

The workplace can be very fraught and complex, so a good level of pragmatism and common sense is fundamental.

For entry-level roles, such as a trainee or junior Health and Safety Advisor, the NEBOSH General Certificate in Occupational Health and Safety is typically required. As your career progresses, obtaining the NEBOSH Diploma in Health and Safety Management becomes essential. At Amentum, we also offer EHS apprenticeships.

Ongoing personal development is also important. Training in process safety, auditing, and behavioural and cultural safety is highly recommended to broaden expertise.

Professionals in this field must be confident communicators, effective leaders and capable of influencing others. Adaptability, empathy, diplomacy and the ability to remain calm under pressure are also key.

Finally, analytical and problem-solving skills are critical – particularly for tasks such as hazard identification and incident investigation. The ability to assess complex situations and develop practical, safe solutions is at the heart of effective EHS work.

What is the biggest challenge for safety in nuclear?

The biggest challenge for safety in nuclear is ensuring the robustness and integrity of facility design throughout its lifecycle. Nuclear safety is a collaborative process that spans concept, design, construction, commissioning, operation and decommissioning.

We mitigate risks through rigorous testing, especially in innovative areas like fusion, where materials such as lithium pose new challenges. Safety is embedded at every stage, supported by strong regulation and a culture of continuous improvement.

What specific safety concerns arise from nuclear facilities?

Nuclear facilities present a range of specific safety concerns, even within a highly regulated environment. These include:

- Ageing infrastructure – many legacy facilities are more than 50 years old. Retrofitting them with modern equipment introduces unique challenges, especially when original design documentation is limited.

- Hazardous materials – at our R&D facility in Warrington, we handle hazardous substances while also conducting construction and engineering work. This requires strict safety protocols and cross-functional collaboration.

- Design replication – much of our work is replicated at other sites, so it’s essential to consider the safety implications for end-users and ensure designs are robust and transferable.

- Compliance with evolving standards – we often work with equipment that was installed decades ago. Ensuring these systems remain compliant with current safety regulations is a continuous challenge.

Collaboration across teams is vital to identify and mitigate risks early in the design and testing phases, ensuring safe and effective outcomes throughout the facility lifecycle.

Do you anticipate the safety concerns changing for nuclear in the future?

I anticipate safety concerns in the nuclear sector will continue to evolve.

- Technological advancements – robotics is playing a growing role in enhancing safety by removing people from hazardous environments. For example, remote inspections now allow us to assess high-risk areas without direct human exposure.

- Innovative safety measures – at our Warrington laboratories, we have introduced Diphoterine, a chemical burn treatment more effective than water, into our emergency response kits, improving our readiness for chemical incidents.

- Emerging materials – our work with advanced materials like lithium and beryllium for fusion introduces new safety challenges. These require rigorous testing and risk assessment from the earliest stages of development.

- Integrated safety culture – from planning through to operations, our EHS and technical teams collaborate to embed safety into every phase of a project. We follow the hierarchy of controls to eliminate or mitigate hazards effectively.

- Human factors – we also place strong emphasis on behavioural safety and mental health. Many tasks require intense focus, so we foster a culture where employees feel supported and empowered to raise safety concerns.

What tips would you offer those, particularly women, who want to get into or develop in this field?

Invest in your personal development and focus on building the key skills needed for success. Strong communication, confidence, adaptability and leadership are all essential in this field.

I’ve been fortunate to have had three mentors at different stages of my career. Each one helped me reflect on my goals and plan my next steps. I highly recommend seeking out a mentor or role model.

If you are already working in a company with an EHS department, don’t hesitate to reach out to a colleague for advice or shadowing opportunities. And for women in particular, connecting with professional networks or women-in-safety groups can be incredibly empowering and supportive.

Be confident in your own ability and don’t be nervous about challenging yourself in the early and mid-part of your career.

David King FIMMM, Head of Safety & Sustainability at energy company Equinor, UK

How did you get into a career in safety in the oil and gas sector and the initiative Step Change in Safety?

In 1992, and soon after the Cullen Inquiry was published into the Piper Alpha disaster, as a young Petroleum Engineer, I had the opportunity to work on the development of the safety cases for a number of Southern North Sea gas fields. This gave me a solid grounding into process safety.

After experience offshore and in operational leadership, in 2005, I was given the opportunity to work with the Baker Panel – an inquiry set up to look at the cultural failures that had led to the Texas City explosion in the US. The Panel was led by the ex-US Secretary of State James Baker and was made up of some of the world’s leading process safety specialists. This opportunity provided me with both the insight and inspiration to fully develop my safety career.

What skills and training were required?

My training as a Petroleum Engineer and certification as a Chartered Engineer via IOM3 formed the foundation, but I supplemented this with a formal NEBOSH qualification. When working in a major accident hazard industry, training is important but front-line experience managing those hazards is, in my opinion, vital to underpin academic training. I was lucky to get that experience through roles as an Offshore Supervisor, Offshore Installation Manager and Asset Manager of offshore oil and gas fields in the North Sea.

What is the biggest challenge for safety in oil and gas?

The foundations of process safety management in the oil and gas industry are built upon the learnings from nearly 40 years of major accidents – Piper Alpha, Exxon Valdez, Texas City and Deepwater Horizon. It is important to keep these learnings alive and relevant for young people coming into our industry, and to ensure new generations of operational and safety professionals in the industry feel the chronic unease to prevent such incidents in the future, as those of us who have lived through these incidents feel.

Over the last two-to-three years, and as demonstrated by data published via Step Change in Safety, the industry has seen a rise in the frequency of hydrocarbon releases and personal injuries. The industry needs to work together to reverse these trends.

What is the biggest challenge you have faced in your career?

Stepping out of the oil and gas industry to lead health and safety in the UK Ministry of Defence for three years. I had the opportunity to work across the armed services and to work with some amazing people, and to carefully introduce some of the tools from the oil and gas industry to reduce the risk of service personnel being harmed during training and exercises.

What specific safety concerns arise in oil and gas?

The fundamental risk in the industry arises from the release of flammable and explosive materials associated with both the extraction and processing of crude oil and natural gas. People sit at the heart of our industry, and it has sadly been the case that human factors have been in the causal chain behind the major events the industry has experienced. As such, the industry, and in particular the leadership, need to focus on building and maintaining a strong safety culture that encourages the following of procedures, the open reporting of hazards and the prioritisation of safety over any other business objective.

Do you anticipate the health and safety concerns changing for oil and gas in the future? What role does Step Change in Safety play in this?

Safety never stops and organisations like Step Change in Safety in the North Sea work hard to prevent process safety events and workforce injuries across the energy industry through active leadership, member collaboration and workforce engagement.

The fundamental risks associated with the industry will endure, but the way we are managing them – and will manage them in the future – will evolve. Technology, especially the robotic and drone-based technology that takes the human out of the hazardous environment, is playing a role today. Going forward, artificial intelligence (AI) will also help in the enhanced identification, assessment and management of risk in the oil and gas industry.

What tips would you offer those who want to get into or develop in the field?

Safety leadership in the oil and gas industry requires a mix of technical expertise, regulatory knowledge and strong communication skills. In addition, building a solid understanding of risk assessment, industry-specific safety standards, and the principles behind human performance and human factors are all essential.

Safety leaders need to influence teams and leadership. Developing skills in effective communication and crisis management ensures that safety is integrated into daily operations. Lastly, gaining front-line operational field experience is very important. Practical exposure to onsite safety challenges provides deeper insights than theory alone.

Dr Jagdish Keshav Jethwa FIMMM, Principal Engineer – Vehicle Safety, at London Electric Vehicle Company Limited

How did you get into vehicle safety engineering?

My passion for Maths and Science led me to study Chemical Engineering at Teesside Polytechnic in 1984. I began my career at Imperial Chemical Industries Wilton, where I worked on a lightweight metal replacement in various industries, including automotive and aerospace.

My early introduction to advanced materials, combined with an MSc from the University of Durham, UK, laid the groundwork for my PhD at Imperial College London, where I researched structural adhesives for vehicle assembly, supported by the Ford Motor Company (USA).

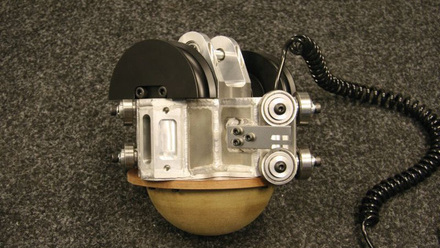

I expanded my materials expertise by working with carbon-fibre composites at the Defense Research Agency, Farnborough. Later, at Autoliv in Havant, I developed automotive safety restraint systems, including seatbelts and airbags, designed to protect occupants in frontal and side-impact collisions.

What skills and training were required?

My foundation in engineering and materials science provided a strong technical base, but specialised training also played a key role. At Autoliv, I trained in mathematical dynamic modelling – a powerful simulation tool to model interactions between crash test dummies and vehicles during collisions.

By integrating simulation with physical crash testing, including multibody dynamics, finite element methods and computational fluid dynamics, we could model and mitigate occupant injuries with high accuracy. This accelerated product development and significantly improved safety system performance.

Mindset is as crucial as technical skills in vehicle safety, where compromise is not an option. Lives depend on systems working within fractions of a second, and as safety engineers, we must always advocate for doing the right thing, even when it is not the easiest, quickest or cheapest option.

What is the biggest challenge of being a vehicle safety engineer?

Balancing safety with competing demands is a constant challenge. New vehicles must deliver excellent crash performance while also meeting targets for emissions, weight reduction, cost, package space and aesthetics, all within tight development timelines.

Perhaps the most difficult, but essential task, is convincing programme managers to prioritise safety early in the development process. While budgets and timelines are constantly under pressure, treating safety as an afterthought can result in costly redesigns and, more importantly, can compromise occupant and pedestrian protection.

What specific safety concerns arise from electric vehicles?

Electric vehicles (EVs) present a distinct set of challenges. Protecting high-voltage battery packs in the event of a crash is paramount, not only for occupant safety, but also to prevent post-collision thermal runaway or fires. This requires integrating battery enclosures into the vehicle’s crash management system, and ensuring the occupant protection cell maintains both strength and stiffness under impact.

Additionally, the placement of heavy batteries alters vehicle mass distribution, which affects crash dynamics and stability. The near-silent operation of EVs also raises concerns for pedestrian and cyclist awareness, especially in urban environments at low speeds. Many countries have addressed this issue through legislation that requires new EVs to have an acoustic vehicle alerting system that emits sound at low speeds.

Do you anticipate the health and safety concerns changing for EVs in the future?

As EV battery technologies evolve and charging infrastructure becomes more widespread, new risks will emerge, including the safety of ultra-fast charging, the management of battery ageing and degradation, and the handling of damaged EVs following accidents, especially by first responders.

We will also need to consider end-of-life scenarios, such as safe battery recycling and disposal, particularly as global EV adoption increases. Regulations are likely to expand to address these areas, and safety engineers will need to stay ahead of both the technology and legislation.

What tips would you give those who want to get into or develop in the field?

Begin with a solid foundation in engineering, whether it be mechanical, electrical, materials or systems – all are relevant. Then look to specialise in fields like crashworthiness, occupant biomechanics, computational simulation or advanced materials science.

Hands-on experience with simulation tools, such as LS-DYNA, MADYMO, or ANSYS, is extremely valuable. Equally important is staying informed about evolving safety regulations and protocols, such as those established by the UN Economic Commission for Europe, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the European New Car Assessment Programme.

Clear communication of complex issues, problem-solving abilities and the courage to advocate for safety are key differentiators.

Embrace curiosity, as many safety advancements arise from interdisciplinary ideas. For instance, airbags rely on chemistry for propellants, permeability-tuneable fabrics for controlled cushioning, physics for assessing impact severity and electrical engineering for sensors. The use of accelerometers and crash algorithms from aerospace technology enables precise deployment to reduce injury risks.

What excites me most is the opportunity to make vehicles safer, not just for their occupants, but for all road users. Advances in active safety, such as autonomous emergency braking, pedestrian detection and driver-assistance systems, are shifting the paradigm from protecting people in crashes to preventing crashes entirely.

As materials, electronics and sensing technologies continue to evolve in tandem with AI, safety engineers will play a crucial role in designing vehicles that can think, react and even learn in real-time. It’s an incredibly dynamic field, and the potential to save lives through innovation has never been greater.

Katherine Evans, Founder of Bold as Brass equity in safety network, Mining Geologist and Assistant Quarry Manager, UK

How did you get into a career focusing on safety in mining geology and quarries?

My career in mining started in 2010 as a graduate mining geologist at Aberpergwm Colliery in Wales, UK. When the coal price dropped, I moved to Canada to work at two sister opencast sites as a pit geologist and production engineer. I did a short stint in consultancy in Cardiff from 2014-16, but then began as a Geotechnical Engineer in quarrying in 2016.

Being Welsh, having worked in coal mining, and being so closely involved with excavations and tips, the Aberfan disaster is never far from my thoughts. Now I’m a parent, it presses that little bit harder, which keeps me focused on geotechnical safety.

What skills and training were required?

I studied Geology at Cardiff University, but I’d say other than learning about structure and stratigraphy during my degree, my role has been almost entirely learnt while working. Stone is an ever-changing natural product, the more you see, the more geotechnical specialists you chat with, the more you learn. That’s what I love about the extractive industry, it’s never boring, it’s constantly changing, there’s always a squiggle in your career to be made.

What is the biggest challenge for safety in the quarrying sector?

I would say complacency. We can become very comfortable in working within hazardous workspaces when we’re in them each day, so it’s important to continue to talk about the hazards, best practice and to refresh our knowledge.

What specific safety concerns arise in geotechnical and quarrying work?

Geotechnical instability of excavations and tips are some of the biggest safety concerns in quarrying, but changes in geology can also affect downstream uses of aggregates that lead to safety issues in construction and on highways. Geologists collect data on rock types that aid the design of the quarries, so we can work out safe long and short-term face angles. The same for tips – all tips are designed and appraised by geotechnical specialists, which includes assessing the surrounding geology, hydrology, landscape and land uses.

Do you anticipate the health and safety concerns changing for quarries in the future?

I think as we move towards automated vehicles with fewer individuals on quarry sites, our safety concerns will focus less heavily on interactions with heavy plant, although I’m sure there will still be need for people on sites for sometime yet as technology and its affordability evolves, given rock is a natural product that can only be predicted to a certain degree of accuracy.

What tips would you offer those who want to get into or develop in the field?

Our industry of quarrying is well hidden and clouded by misinformation, people rarely get to see our world of career possibilities. For anyone looking to work in sustainability it’s a brilliant place to be. If you’d like to see what we do, get yourself to a quarry open day, you’ll be amazed by the vastness of career opportunities available, the scale of what we do, and the lengths we go to keep our communities and local environment safe, clean and healthy.

Championing equity in personal protective equipment

Katherine Evans’ Bold as Brass campaign for equity in personal protective equipment (PPE) is about helping to develop the first P in PPE – personal, for everyone, regardless of sex, gender, body size, race, ethnicity, neurotype, disability or health.Evans has been a geologist for 17 years, now Assistant Quarry Manager. Needing to be out of the office much of the time, she knew how often people like her didn’t feel their working environment was set up for them to survive, let alone thrive in. She saw PPE as a simple problem to fix.

She wanted to shine a light on the PPE that was available to people who were anything but the average worker. It started with women, but spread very quickly to all minority groups in heavy industry. She wanted to feed real experiences back to PPE designers, 'so they could develop better fitting products that allow everyone onsite to achieve their full potential'.

She collected information around the PPE-related issues being experienced by women in heavy industries, as well as linking up with advocates to share trends.

She got in touch with PPE brands working in the UK to pass over the trends and find out what they had available. The discussion stretched further than women’s PPE into all PPE.

Evans reflects, 'The female body differs from the male – it carries out very different functions, but this is often overlooked by non-diverse, decision-making groups, or embarrassment about talking about periods, irritable bowel syndrome and urinary tract infections (UTIs).

'Working away from welfare facilities isn’t as safe or easy for a person managing a period, especially when a period could lead to toxic shock syndrome or sepsis. The process of having children, ageing and menopausal hormonal changes affects the female body in a very different way to a male – from UTIs, partial and total incontinence, reducing bone and ligament strength, and drops in collagen production – the female body is more likely to be injured and stay injured longer.'

She continues, 'Among other challenges, if PPE doesn’t fit, then you aren’t able to carry out your job to the best of your ability, it then begins to become a new safety concern, as well as a career development hindrance. Your head is distracted when you’re focusing on pain, discomfort, or keeping PPE on that’s about to fall off. There’s also the increased concern of blood leaks during your period or flooding event during perimenopause. Hi vis PPE shows blood very well, and although there should be zero shame in blood leaks, we live in a society that still assigns shame. The distraction can take a person’s focus away from the safety critical environment.'

She believes there is a movement away from solely focusing on the hazards towards including the different characteristics of individuals when attempting to reduce risk. 'We already do this to a degree, but we are gaining a better understanding of intersections.'

She suggests the leaders of industry need to create a listen-up culture based around a growth mindset, psychosocial safety and an understanding of systemic discrimination. 'If we want to see our heavy industries modernise at the rate of other industries, we need to keep up with the pace of societal change, listening to understand instead of listening to respond is the start.'