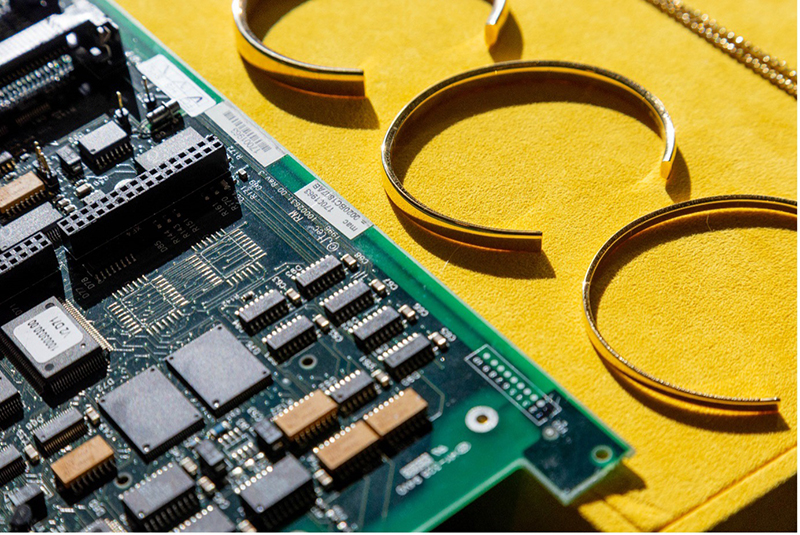

The Royal Mint extracts gold from waste electronics

The Royal Mint’s new factory in South Wales will extract gold from e-waste and reduce reliance on virgin materials through mining.

Electronic waste (e-waste) is the world’s fastest-growing waste stream.

As consumption of electronics soars, so does e-waste. Electronics recycling, however, is currently a long way from keeping pace. The financial, material and emissions costs of this are enormous.

Now, The Royal Mint is applying its 1,100 years of metal-working expertise to scale up an innovative technology from laboratory to an industrial level and tackle the problem.

Its new Precious Metals Recovery factory in South Wales repurposes one of the oldest currency manufacturing areas onsite into a 3,700m2 facility that extracts and recycles 99%+ gold from printed circuit boards (PCBs) used in everyday items, such as TVs, laptops and mobile phones.

The facility uses a patented technique from Canadian company Excir to extract the gold from PCBs in minutes. It is estimated that the new factory can process up to 4,000t of waste PCBs every year. On average, 1t of PCBs produces around 165g of gold, worth about £9k.

Working to full annual capacity, the factory would recover around half a tonne of gold, 1,000t of copper, 2.5t of silver and 50-60kg of palladium.

The feedstock comes from various sources, including IT original equipment manufacturers, IT Asset Disposition companies, the Ministry of Defence, and Approve, Authorised Treatment Facilities, which sort IT hardware from local recycling centres.

Precious recovery

Each PCB undergoes several processes for reverse engineering. First, the components are removed from the boards before the materials are sorted into multiple streams. The PCBs are then prepared for metal extraction. The gold-rich parts are transported to a chemical processing plant, where they are loaded into a reactor using Excir’s proprietary technology that leaches the gold. Precipitation and filtration removes the leached gold from the liquid solution, which can be reused and purified into a gold powder.

This powder is further refined and melted in a furnace to create a high-purity ingot for The Royal Mint’s 886 jewellery collection. The plan is to eventually use the recycled gold across a range of other products, such as commemorative coins.

Sean Millard, Chief Growth Officer at The Royal Mint, explains that Excir’s chemistry yields the best recovery levels with a high-purity metal that needs no further refining.

Additionally, it operates at room temperature, further reducing emissions, which is part of The Royal Mint’s wider strategy.

'The whole process is rooted in sustainability,' Millard says. 'Materials that don’t contain gold aren’t simply discarded. We sort the remaining material into various fractions to recover copper, steel and aluminium. We also send plastics and fibreglass composites to a local business who turns them into building materials.

'The non-precious metals that we recover (copper, tin, steel and aluminium) will go to other companies as a raw material to turn them into products such as sheets/bars/rods to manufacture new products.'

Millard continues, 'For us, expanding into precious metals recovery is a natural progression. With over 1,100 years of expertise in working with precious metals, we’re able to bring a wealth of skills to this new venture. But this isn’t just about gold recovery – it’s about preserving the craftsmanship, jobs and legacy The Royal Mint is known for. As we evolve for the future, our focus on sustainability and innovation drives every aspect of our growth, to ensure we’re around for another 1,100 years.'

In 2023, the organisation took a significant step into the precious metals recovery industry by partnering with Betts Metals. Through this collaboration, they began using silver sourced entirely from recycled medical X-ray films in their 886 jewellery collection.

'As we explored further opportunities to expand in this area, our focus was to ensure that any solutions we adopted aligned with our commitment to sustainability and responsible sourcing,' adds Millard.

The Royal Mint considered a wide range of technologies before concluding that Excir was its preferred technology partner.

- More than 50Mt of electronic waste is produced globally per annum.

- A record 62Mt of e-waste was produced in 2022, up 82% from 2010. This is set to rise another 32% to 82Mt in 2030.

- Only 17% of e-waste is formally recycled worldwide.

- The UK is one of the worst offenders, generating the second highest amount of e-waste per capita in the world, with 24kg.

- UK households are holding onto 880 million unused electrical items and throwing away 103,000t.

Source: The Global E-waste Monitor 2024 and research on Electrical Waste: Challenges and Opportunities from Material Focus

High stakes

Millard explains that the UK currently generates the second highest amount of e-waste per capita globally, with most of the UK’s waste circuit boards exported to Europe and Asia to be smelted at high temperatures. This process creates thousands of additional ‘waste’ miles, produces more CO2 and uses vast amounts of energy.

Currently, gold, silver, copper, palladium and other highly valued metals, which market research from The Global E-waste Monitor 2024 conservatively values at US$57bln, are mostly discarded as opposed to being collected for treatment and reuse. In addition to the waste and lost opportunity, single-use electronics frequently create environmentally hazardous waste.

The same research suggests that nearly £1bln worth of precious materials could be saved if all UK electricals were recycled.

The new facility 'addresses this growing global problem, while allowing us to reduce our own reliance on mined materials and providing us with a sustainable source of gold to use in our products', Millard says.

'Every step of the process has been tested extensively and our technicians and chemists have poured everything into making our new facility a success. The factory is bespoke to The Royal Mint, and we’ve worked with partners big and small to create something unique.'

The Royal Mint is also working with Excir on a chemical process to extract other valuable metals, including palladium, silver and tin from PCBs. Moreover, it is hoped this factory will help make the UK a world leader in sustainable precious metals recovery and circular economic practices, while also creating jobs and allowing colleagues to reskill.

The new facility in South Wales could serve as the blueprint, with the organisation exploring ways to scale the model, both in the UK and internationally.

Millard concludes, 'Our goal is to establish small, energy-efficient plants around the world, encouraging greater e-waste recycling by lowering costs and offering a more convenient alternative to overseas shipping for companies.'