Engineering inclusive outcomes

Dawn Bonfield MBE, FREng, FIMMM, Visiting Professor of Inclusive Engineering at Aston University, UK, champions an Inclusive Engineering Framework that keeps all end-users in mind.

If you have been working in the field of engineering over the past five years, you will have likely noticed the growing emergence and importance placed on the topics of diversity and inclusion in our sector.

If you are in any kind of management role, then no doubt you have considered various responses to increasing the diversity of your workforce, and the inclusiveness of your business or department. I imagine too that you are familiar with the business case for taking this action. But have you ever stopped to think about the inclusiveness of what we produce as engineers?

This topic is known as inclusive engineering outcomes – the discipline of ensuring that engineering products and services are accessible and inclusive of all users, and are as free as possible from discrimination and bias. In short, our engineering solutions need to be appropriate, ethical, accessible, sustainable, responsible, and work to ensure that nobody is left behind – and while this is made easier with a diverse workforce, the two topics are not the same.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been largely responsible for more widespread understanding that the world we have built is not equal for all members of society. As the pandemic progressed, different groups of people experienced different outcomes as a direct result of the structural inequalities of their surroundings, specifically about access to green space and city design, which is clearly not accessible for all.

Thinking about the built environment more broadly, there are many groups of people who do not feel equally included in their surroundings. As an example, the arguments around decolonisation have thrown up difficult decisions and differing viewpoints about whether we should erase the historic references to a colonial past from one perspective within the built environment, or if we should retain the history but retell and reframe the narratives, and acknowledge the colonial legacy.

Another example relates to a better understanding of how people use the services in cities, such as the public transport system, and a realisation that a system – while equally available to all on first glance – is anything but equal when the experiences of different user groups are fore fronted and their user journeys are analysed.

Those with caring responsibilities, for example, use transport systems in a way that any inefficiencies in the system become multiplied and burdensome due to their shorter and more frequent journeys. This is compared to those who have simple point-to-point journeys where inefficiencies can be absorbed more easily. It’s the difference between equality of service provision versus equality of service outcome, which anyone who has experienced the queues for female public toilets can relate to.

But beyond the more obvious analysis of our services, there are many other examples of inequalities in our systems. Digital technologies, data, artificial intelligence and machine learning provide many opportunities for bias to be built into our systems or, more accurately, to remain in our systems.

Take an example of machine learning to create legal documents, or to make decisions related to criminal justice or loan agreements. Or how women are shown more job adverts for nursing than engineering, or why minoritised candidates are not shortlisted for roles ‘non-traditional’ for their group.

There are biases here that are rarely built-in deliberately – although they are in some cases – but are the result of historical datasets that do not reflect the world as we see it today.

Criminal convictions meanwhile are influenced by policies like racially profiled stop and search, resulting in more fingerprint and DNA samples being collected from black and ethnic minority communities than white communities, resulting in a greater likelihood of a criminal conviction in one community than another.

The examples above are all relatively easy and straightforward to see. To prevent this level of bias and discrimination from creeping into these solutions, it takes an awareness of the risks and a commitment to prevent its occurrence – albeit that this is sometimes easier said than done when biases are so embedded in data.

But some inequalities are much harder to see, and this is where we need more sophisticated frameworks to understand the risks.

For example, are we guilty of consigning the developing world to a future of devastating climate change as a result of the carbon emitted by our advanced technology needs, while we continue – for the time being at least – to experience much fewer harmful impacts?

We now have a much greater requirement to ensure that solutions leave no one behind and are inclusive of all more than ever before, and we need to start to take these outcomes into account at the earliest possible parts of our solution, product or process design.

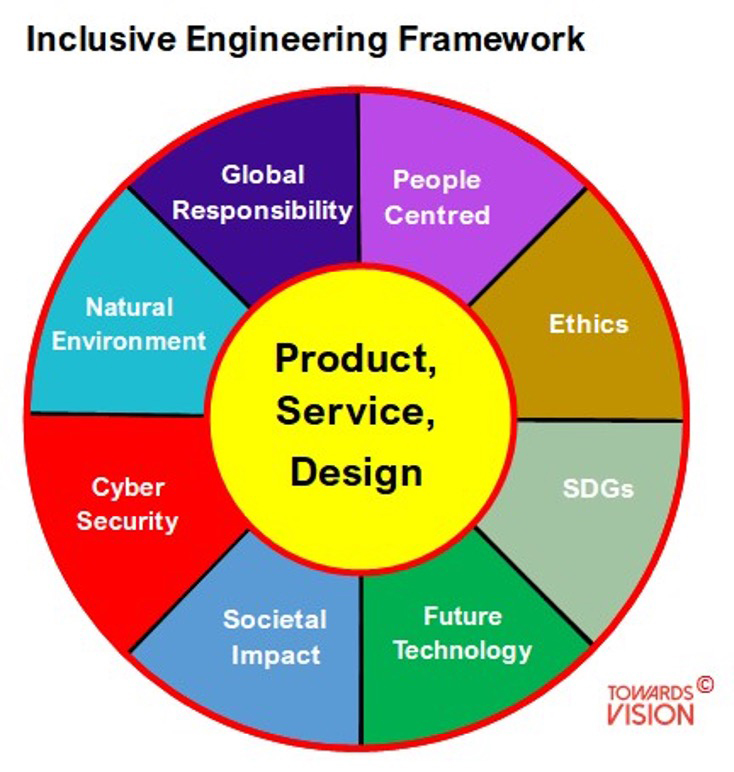

The Inclusive Engineering Framework (see image below) allows these holistic and systems decisions to become more visible at the start of projects. In addition to the people centred designs discussed above, we as materials engineers must also consider a number of other non-technical considerations in our decision making.

Technology solutions can – if designed appropriately – also address pressing societal issues at the same time in a multiplicity of ways, such as using domestic hydrogen energy delivery to create active travel solutions, or deliver digital services to an ageing population – and in this way deliver more societal impact.

New solutions need to be future technology ready, requiring a knowledge of whole connected systems, where solutions are complex and multifunctional. The interconnectedness of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals requires broad understanding if we are to ensure that progress is made across the board and not in one area at the expense of others. Nature, biodiversity and the environment need to be present in every decision as a key stakeholder, whose needs should be prioritised and given a voice.

Of course, ethics and our global responsibilities, such as the use of appropriate technology, cultural competence, and respect for local and indigenous populations, are key to our roles as professional engineers, and we must have these at the forefront of our mind and embedded in our design solutions.

An increased awareness of the cyber and digital security of our products is vital to build in from the start of any solution design, as the development of malicious and harmful products requires robust defence to tackle the changing and increasingly sophisticated cyber threats.

Engineering is becoming a much more complex and interconnected discipline where compromised solutions to wicked problems are increasingly the norm, so to solve these problems, we need to find decision making processes – like the Inclusive Engineering Framework – that remind us how to design, so that our solutions are robust, inclusive, and accessible to all, and where we have eliminated embedding bias and discrimination.