Golf-ball coating is hole-in-one

A coating can reportedly slow down or speed up a golf ball by soaking up water molecules without interfering with the ball’s aerodynamics.

The invention comes from polymer chemist Thomas J Kennedy III, owner of Chemical Innovative Solutions Inc, USA.

He previously developed golf balls that optimised long-distance performance in the air. But with his new project, he focuses on the interaction between the ball and the grass.

A dry putting green can help the ball soar at lightning-fast speed, but wet grass creates an almost sticky runway. So, Kennedy created a hydrophilic coating that modifies the surface-to-surface interaction between the ball and the green.

'I was thinking about a way to help golfers and the game of golf overall by improving the putting process, so that having a good round was not a matter of chance but a matter of skill,' says Kennedy.

The coating increases the ball’s surface energy. Instead of beading up, water absorbs or sheets off the surface. On dry grass, the coating draws up water to slow down the ball. On wet grass, the coating helps release the green’s grip on the ball.

It contains absorbent amorphous silica, molecular sieves, clay and fast-exfoliating polyacrylic acid polymer.

Kennedy has tuned the molecular sieves to only absorb water-sized molecules. He has also varied the ratios of absorbent compounds to create a coating that reportedly provides the right amount of traction, but does not impact the ball’s flight once it’s launched into the air.

He explains that, while there is a limit on size and weight, a symmetry constraint, and a standard for overall distance travelled, there is latitude to change the playability of golf balls, while staying within the confines of the rules of the US Golf Association and the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews.

To test the coating’s effect on fast and slow greens, Kennedy employed a Stimpmeter – a V-shaped metal rod that applies a known velocity to the ball. By using the rod as a ramp for rolling a coated or uncoated ball, the distance it travels on a dry or wet green can be measured and compared.

Experiments suggest the coated balls have a more consistent speed on both dry and wet simulated greens compared to uncoated ones.

Kennedy believes the coating would boost a player’s already-honed skills. For the average golfer, this could mean finishing 18 holes on par. For the professional, it could result in fewer strokes and greater prize money.

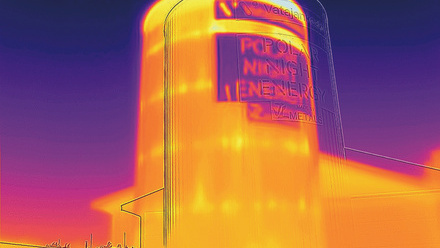

Kennedy also thinks the coating could be applied to solar panels to improve their performance. 'It may sound counterintuitive,' he explains, 'but the hydrophilic nature of the coating keeps solar panels cleaner by allowing water to soak the surface and wash away sun-blocking dust and debris.'

He currently has provisional patents for use of the hydrophilic coating on both golf balls and solar panels.

'The game of golf has been around since the 15th Century. However, there’s always a new way to look at something as technology evolves,' he reflects.