Fred Starr recollects: Digging deeper

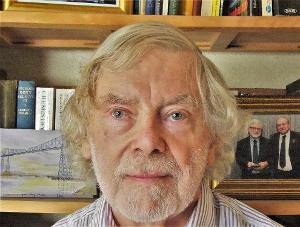

Fred Starr FIMMM recalls how a microbiologist saved the UK’s gas storage sites from disaster.

The Beirut catastrophe brings to mind Canvey Methane Terminal, on the Thames Estuary, where the storage of LNG (liquefied natural gas) was an energetic equivalent to six Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs. Where, in a very small way, I helped prevent a potential calamity.

The real hero was British Gas’ Head Microbiologist, Dr Eileen Pankhurst, who, despite her name and resemblance in character and appearance, was no relation to the champion for women’s rights.

Inching towards disaster

LNG needs to be stored at -173°C, and when our Methane Terminal went into operation, it was stored in six large, insulated, cylindrical tanks, all above ground. If the tanks ruptured, LNG would flood across the island and estuary, mixing with air, forming an explosive mixture 12 times more violent than trinitrotoluene (TNT).

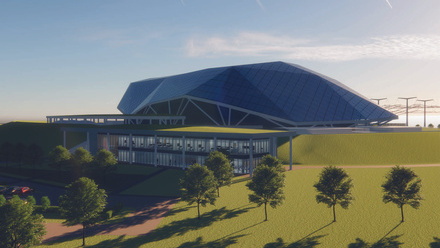

The Terminal, the first in the world, was very successful, with more storage being needed. British Gas turned to the idea of digging four huge holes in the ground, lining them with concrete, giving an extra 80,000t of capacity – a terrorist-proof solution. Far safer than an above-ground conventional tank farm.

The drawback emerged after the tanks were filled. An ‘ice shell’ was beginning to surround the tanks as the ground froze. This was anticipated. What wasn’t expected was that as the ground water froze and expanded, the area surrounding the tanks began heaving upwards and sideways. The mess that was made of roadways was regarded as rather amusing, until the realisation dawned that the ice shell was heading towards the tank farm. If the foundations of these tanks cracked, causing collapse, it would be ‘hell on earth’.

Eileen’s interjection

Canvey personnel had a solution and were proud of it. They had sunk a set of pipes around one of the in-ground tanks, through which a warmed mixture of water and antifreeze was circulated, holding back further expansion of the ice ring. A group of researchers, including Eileen and myself, had been invited down to Canvey to see this ‘heat barrier’ marvel, where the input and output to the pipes came out into a large open tank.

The tank, the size of a bath, was full of brown and green sludge. It was, to almost all of us, one of the least interesting things we had ever seen. But not to Eileen. In the acerbic manner, for which she was so famed and feared, rhetorically she asked, didn’t anyone at Canvey comprehend that the components of the antifreeze, ethylene glycol, phosphates and nitrates provided the perfect food for bacterial slimes? It was only a matter of time before the heat barrier blocked up. When it did, the barrier would itself freeze solid and the ice ring would continue its march of destruction.

What to do? The pipework was so slime ridden that normal biocides would be useless. I advanced the idea that a shot of hydrochloric acid would see the end of the bugs and Canvey’s troubles. It did, but we needed two tanker loads of acid.

Another pinch of salt

Eileen was brought in too late on another job, involving Britain’s first salt-cavern gas storage site at Hornsea, close to the Yorkshire coast. The cavern, 2km deep, located in the Zechstein salt strata, had been ‘excavated’ by piping in seawater, dissolving out the salt. Unfortunately, the pipeline bringing in the sea water was clogging up with barnacles and mussels. Could Eileen suggest something, bearing in mind that since the return flow was back to the sea, there were severe environmental constraints?

She could. But if she had been asked earlier, there would have been no need for biocides. If the flows in the input and output pipes had been periodically switched over, these pestilential creatures would, every so often, have got a slug of extremely salty water, wiping them out and washing them back to where they came from.

Underground excavation – a novel approach.

The intention was to ‘open up’ the gas reservoir at Lockton, under the Yorkshire Moors, using an atomic bomb, the reservoir having run dry. It was a proposal of Grev Gibson, one of the people who got Canvey started. Serious work was done on the scheme, getting the Atomic Weapons Establishment, at Aldermaston, to redesign a bomb that would go down the drill pipe. Grev had looked into radiation contamination of the gas, and how big the bang would be. Neither was an issue he claimed.

Sadly, the idea was squashed by more lily-livered souls. As a 1960s technocrat, half of me wishes it had gone ahead. My other half, with environmental leanings, is relieved that the project died. If successful, North Sea Oil Fields would have been opened up in a most unusual way.