Africa’s mining sector

From large-scale projects to small artisanal set-ups, Africa’s mining sector boosts the continent’s GDP and can make a difference to the lives of small, local communities. Mark Kenwright, Associate Director at Wardell Armstrong International, explains more and how these two halves may come together.

Mining can be a significant portion, if not most, of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for some African countries. Therefore, mining could, and should, be a primary driver for economic growth and a focused area of government policy to be a catalyst for economic change.

Given the large capital costs of a new mine (US$50mln-US$1,000mln) and the typical timelines to develop a mine (seven to 15 years), there is a significant lag and uncertainty as to when, and if, mines will come online. As such, governments and communities can be frustrated with the apparent lack of progress. Juxtaposed against large mining projects, artisanal mining is a semi-permanent, but nomadic industry, that exists throughout Africa and beyond.

A catalyst for advancement

Governments and communities generally welcome large-scale mines as they provide much needed investment and employment. Mining in Mongolia, for example, contributes around one-third of GDP and accounts for 89.2% of the country’s total exports. GDP is projected to be 36.4% greater in 2019 because of its Oyu Tolgoi mine.

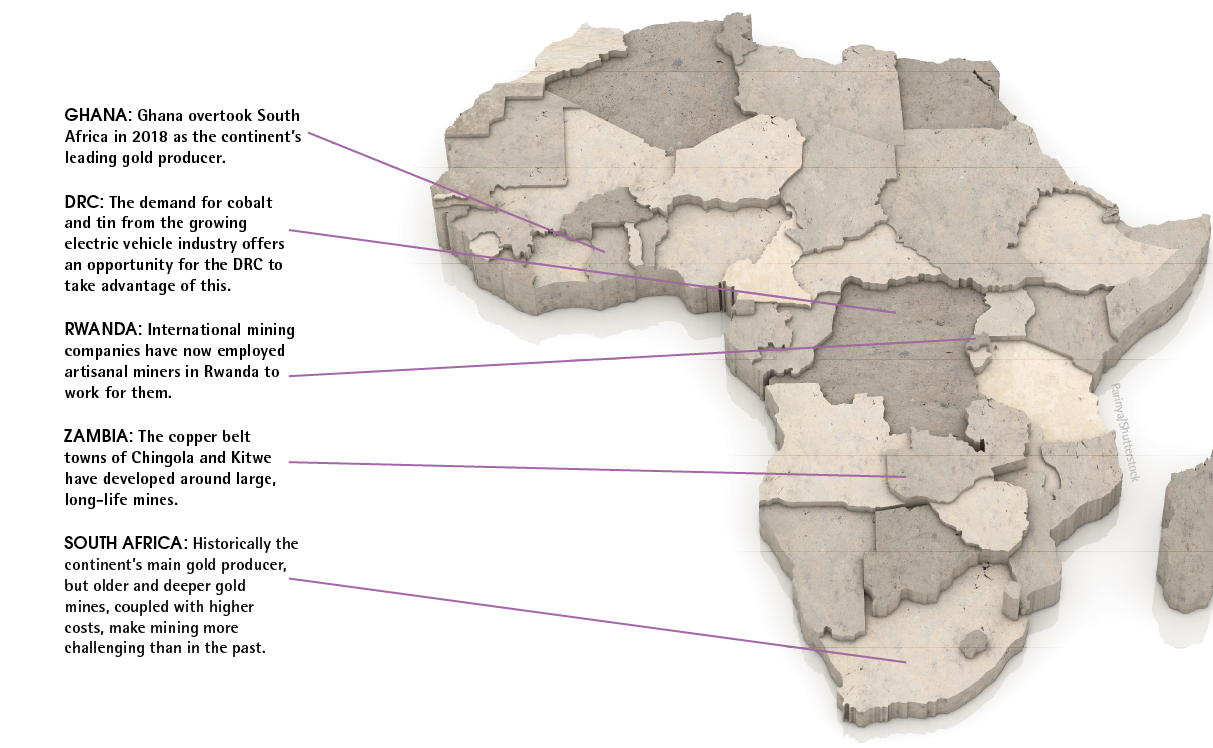

Elsewhere in Ghana, a report from The World Bank shows the country has surpassed South Africa as the leading producer of gold in Africa - exporting 158t in 2018, a 15% increase over the previous year. The mining sector contributed GH¢15.8bln (US$2.8bln) and GH¢17.1bln (US$3bln) in 2016 and 2017, respectively. The industry is proving to be one of the largest sources of revenue to the government as mineral royalties, corporate taxes and employee income taxes play pivotal roles in collecting revenue.

Clearly, mining and exploration can jump-start economies, as well as act as catalysts for increased training, skills and knowledge and advancement for citizens.

Impact on communities

Mining companies provide much needed employment in communities, and the increasing national prevalence of replacing expats with locals who are suitably trained will likely increase the standard of training more generally.

Many of the mines are also in poor remote areas where even the basic living standards such as clean running water and functioning toilets are scarce. There are typically no medical facilities, meaning minor injuries can become infected and serious road traffic accidents fatal. Mines are typically seen by community leaders to bring schools, roads, jobs and clinics into the area.

In the past, mining development companies would build whole towns around projects, for example, the copper belt towns of Chingola and Kitwe in Zambia and Kolwezi in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are large towns that have developed around large long-life mines. However, mining companies are now hesitant to commit to large projects as the taxes and royalties paid by companies are what should be used to develop facilities. Nevertheless, providing such facilities for the mine workforce (and sometimes their dependants) is not uncommon, in fact, it is required.

Mines also provide employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for local businesses that range from food, building materials and services. These activities not only benefit the community but also keep workers and their families supported through better living standards.

Mines have improved their community engagement and this is something that has to continue, especially in light of recent disasters such as the tailings dam failure and resultant deaths in Brazil. The ever-present danger in West Africa of terrorism is one area where intelligence shared means less risk to both the communities and mines.

It should be noted that mines do not continue forever – they can last for six years, though typically it is 10 years or more. Once a mine is depleted, it is then rehabilitated, the equipment sold and employment ends. As part of the Environment, Social and Governance strategy, mines provide some form of business development to continue in the area once they have left, normally in the form of training, or assisting in local farming. These efforts can have mixed results, especially in more remote areas where the mine can act as a centre for economic development, but once it is gone, the hub evaporates.

In comparison to artisanal mines, large-scale projects can offer considerable advantages, including the opportunity of full-time employment for between 300-1,000 direct employees, with a multiple of that used as indirect employees.

There is also improved health of the surrounding community due to food security and medical clinic provision, as well as improved education for children, adult education and training, with opportunities for women to advance through employment at the mines or generally through a better lifestyle that the extra income brings.

As the mine is developed, and exists as an ongoing business, there is considerable skills transfer and opportunity from expats brought in to start and run the mine to local employees. There is significant receipt of taxes at local and national levels. These investments also include improved infrastructure to enable construction of a large mine, and more sustainable and secure income for national government to plan large policy implementation.

Artisanal mining in the DRC

The DRC is a vast country where artisanal mining is prevalent in all main mining areas including gold, copper, cobalt, diamond and other metals. Many communities have been engaged in artisanal mining for generations, even thousands of years, and consider the mined metals ‘as theirs’.

Artisanal mining can, except for informal agriculture, be the only form of income for communities, especially those less educated, and for more vulnerable women and children who are less mobile in their ability to search for employment.

Therefore, by participating in artisanal mining in their local area, much needed income can be earned, notwithstanding the health and personal security risks. Where mining and exploration companies can provide employment, especially in remote areas, this can often be the first full-time employment opportunity available.

Source of conflict

There is a disconnect between local community development and centralised government collection and disbursement of funds (or lack thereof). This can lead to conflict between companies who have been awarded mineral rights and local communities who have operated in the region for years and who are now being requested to move on.

However, mining and exploration companies are improving when it comes to interacting with artisanal miners. For example, in Rwanda, international companies have employed artisanal miners to work for them – an approach that appears to be working well.

In the DRC, Trafigura, the mining project owner and developer is currently collaborating with the country’s authorities and appears to be moving forward with a plan to integrate all artisanal mineral production for the copper and cobalt sector into a new parastatal in an effort to control production and maximise revenue.

Wardell Armstrong International (WAI) observed a worrying set-up of artisanal mining involving cyanide, with workers washing gold concentrate, then adding a cyanide solution to produce a concentrated gold pregnant solution. A zinc foil is then added, with gold precipitating onto it. WAI observed an abandoned 12-cell unit with four cells for the pregnant solution – this is a significant use of advanced chemistry in the treatment of gold ore and gold production.

Alleviating poverty

WAI also notes the importance of artisanal mining particularly in cobalt production, which is vital to alleviate poverty. The DRC Government is attempting to formalise this informal mining sector, and to provide pathways to break the cycle of slavery. The government hopes to increase royalties and taxes from the minerals sector, provide improved opportunities for individual and communities, especially in the employment, education, training and empowerment of women.

Industry regulation should lead to less corruption, less smuggling of cobalt ore and concentrate, with more transparency in government spending and accountability.

Minerals have become an important source of revenue in DRC, highlighting a potential source of growth, especially in cobalt, copper tin, tantalum gold, with ore concentrates selling for millions of US dollars. As well as cobalt, the need for tin has increased over the last decade as technology progresses.

In terms of the electric vehicle industry, while cobalt is a key ingredient of batteries, tin has been described as ‘the glue that holds electric batteries together’. Importantly, without tin, electric batteries could simply not be made. Hence, the demand and price of both cobalt and tin should be positive, and the DRC and the Greatlakes countries in general should position themselves to take advantage of this.

The future of artisanal mining?

There is a willingness to engage with the artisanal mining sector. There have been moves by governments and other world bodies, including The World Bank, to integrate artisanal mining and capture the production of metal such as cobalt in the DRC, with recent initiatives to compensate miners for financial loss during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is clear large mining projects are very attractive to governments and communities provided the social licence to operate is secured. However, in the absence of other income-producing opportunities and in poorly regulated and remote locations, artisanal mining will continue as the only means of providing an income aside from subsistence farming.