Imaging study reveals how atoms are packed in amorphous materials

Study shows how fundamental building blocks of substances are assembled.

A research team, led by scientists at UCLA, USA, has developed a method to map atomic structure in three dimensions. The scientists have directly observed how atoms are packed in samples of amorphous materials.

The findings, published in Nature Materials, could inform the design of future materials and devices using these substances, the team says. Many substances are arranged into crystals. Because their molecules are laid out in an orderly, repetitive pattern, much is understood about their structure. However, a far greater number of substances - including rubber, glass and most liquids - lack that fundamental order throughout, making it difficult to determine their molecular structure. To date, understanding of these amorphous substances has been based almost entirely on theoretical models and indirect experiments.

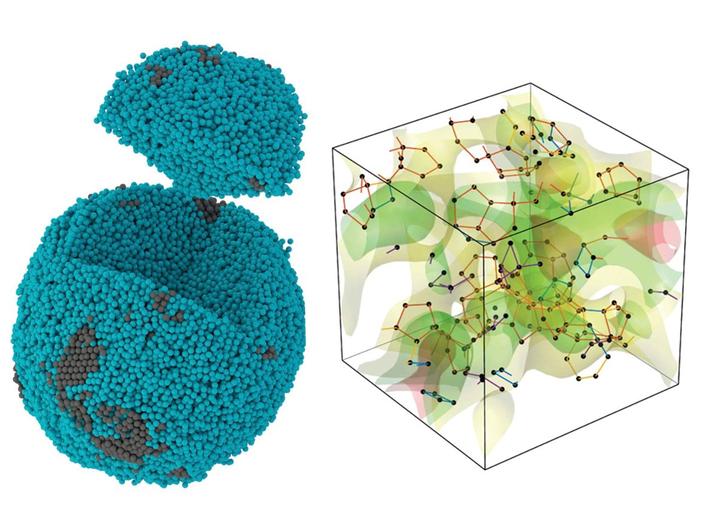

Prevailing scientific understanding has been that atoms and molecules in a liquid or amorphous solid generally fit together into groups of 13. The model holds that they are configured with one central atom or molecule surrounded by the other 12 — two rings of five around the central particle, with another one capping the top and one capping the bottom.

To model how clumps of atoms or molecules could fit together at larger scales, scientists conceptualize this group of 13 as a 3D shape by treating each outer particle as a corner and connecting the dots, resulting in a solid with 20 triangular faces, called an icosahedron.

The team analysed three amorphous metallic objects using atomic electron tomography. This a powerful imaging method beams electrons at a sample and measures the electrons as they pass through, capturing data multiple times as the sample is rotated so that computer algorithms can construct a 3D image.

The researchers discovered that only a very small fraction of the atoms formed icosahedral groups of 13. Rather, the most seen arrangement was groups of seven, with five in one central layer, one on top, one on the bottom and no central atom — a shape the researchers describe as a pentagonal bipyramid, having 10 triangular faces. They also observed that these pentagonal bipyramids formed into networks in which edges were often shared.

The predominance of that combination was consistent across the samples studied by the researchers, who, for simplicity’s sake, selected materials that exist as single atoms at their fundamental scale. The materials examined were a thin film made from tantalum, which is a rare metal used for electronic components, and two nanoparticles made from palladium, a metal important for the catalytic converters that render automobile exhaust less toxic.

The team also used their experimental data as the basis for a computer simulation of what happens when tantalum is melted then quickly cooled so that crystals don’t form, resulting in what’s called a metallic glass. In the simulation, the atoms of tantalum similarly packed into networks of pentagonal bipyramids more often than any other shape, both as a liquid and a glass.

We believe this study is going to have a very important impact on the future understanding of amorphous solids and liquids - which are among the most abundant substances on Earth,' said the study’s senior author, Jianwei “John” Miao, a UCLA professor of physics and astronomy and a member of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. “Understanding the fundamental structures may lead to dramatic advances in technology.'

These findings may prompt a reconsideration of certain aspects of science’s physical model for the world around us. And because amorphous materials are integrated into certain semiconductors and numerous devices, including solar panels, this research could be an early step to replacing trial and error with purposeful design where these materials are involved.